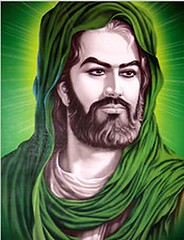

There are two major strands of Islam - Sunni and Shia. The vast majority of the world's Muslims are Sunni. The name Shia is a contraction of Shiat Ali, the Party of Ali. Most of the population of Iran profess Shia Islam - it's the only country in the world with a majority Shia population, which isn't surprising, as this is the region in which Shia Islam emerged.

Imagine if Jesus had had a daughter and the Apostles had killed her offspring in order to retain control of the nascent Christian church; assuming you're a Christian or were brought up as such, that gives you an indication of the depth of the schism between Sunni and Shia Islam.

Despite inauspicious beginnings, the Prophet Muhammad became a rich and powerful man during his lifetime; he commanded armies and had access to vast wealth. He gathered around him a powerful cadre of followers, many of which were family. None of Muhammad's sons outlived him or reached adulthood, but one of his daughters, Fatima, did. Fatima was married to a cousin of Muhammad's named Ali and bore two sons, Hasan and Husayn.

After Muhammad's death, a power struggle emerged between his followers as to who should be his successor, or Khalifah (rendered in English as Caliph). Many of Muhammad's followers believed that the prophet's message should be passed on by his father-in-law, Abu Bakr. A smaller faction gathered around Fatima's husband, Ali.

Abu Bakr took the role of Caliph and a bitter feud broke out between to two factions, which lasted for years, Ali refusing to swear allegiance to Abu Bakr. Abu Bakr was followed as Caliph by Omar and Uthman.

Uthman was murdered in a violent uprising and Ali took control of the Caliphate after a protracted battle with Muawiyah, another of Muhammad's followers, a fierce warrior who commanded considerable armies.

Ali in turn was assassinated (and is now regarded by Shia as the first Imam) and replaced as Caliph by Muawiyah. The struggle for control of the Caliphate was taken up by Ali's son Hasan (grandson of Muhammad). Hasan was poisoned (becoming the second Shia Imam) and the fight fell to his brother Husayn, who fled with his extended family and supporters from Medina to Mecca and gathered support from the population of the town of Kufa, who had risen up in revolt against the hereditary succession established by Muawiyah and had requested Husayn to become their Imam.

Muawiyah's son Yazid had taken control of the Caliphate, suppressed the uprising at Kufa and took control of the city. Despite this, Husayn and just over one hundred of his followers started on the journey to Kufa, but were intercepted by the governor of Kufa and his army of between 30,000 and 200,000 men at Karbala, where the majority of the party were slaughtered, their remains left unburied and the women and children taken captive.

The battle of Karbala marked the decisive point at which Sunni and Shia Islam went their separate ways; the two grouping have never been reconciled since. The slaughter of Husayn (later designated the third Shia Imam) is commemorated every year in Iran at the festival of Ashura, the culmination of the mourning month of Moharram.

29 January 2009

05 January 2009

Flickr Collection coming together...

Now that we're back, we've been filtering our 3,000-odd photos and putting a selection up on Flickr. The places we visited were fascinating and often awe-inspiring, but I have to say it again: it was the Iranian people whom we met who made our trip so utterly memorable.

Abuse of power

One of the most important encounters of our time in Iran has been the hardest one to blog about. I've changed the names of the two people involved and removed all of the possibly identifying detail which I'd originally intended to include. You'll understand why.

One afternoon, Aisling and I bumped into a father and his teenage daughter. Dad was carrying a bag of groceries. After exchanging the usual pleasantries, dad invited us to have lunch with them. "That'd be lovely," Aisling replied.

We walked on together, introducing ourselves. Dad's name is Firouz, his daughter Hengameh. Hengameh's English is good, Firouz's more rudimentary.

We arrived at their house and Firouz busied himself preparing first chay for everyone and later, lunch. As we sat around drinking chay, Firouz asked, "what's your opinion of the Iranian government?"

I tried to give a diplomatic reply, along the lines that in European media we read a very one-dimensional view of Iran, so part of the reason for our visit was to talk to ordinary Iranians to find out what the real story is. Firouz saw my reply for what it was, an attempt to side-step the question, chuckled, and then began slowly revealing his own opinion on Iranian politics and describing his experiences under the theocratic regime since the 1979 revolution.

Firouz was a young teacher at the time - in his early twenties - and was politically active. When the Islamic revolutionaries gained the upper hand, he was sacked from his job. Worse things happened, but I'm not going to mention those details - they could be used to identify the people concerned.

All of this was mediated through Hengameh, who's fourteen.

Firouz didn't volunteer the information that he'd been tortured. I'd asked. Hengameh didn't know what the English word 'torture' meant, so I said "Bastinado?"

"Hah!" exclaimed Firouz and looked at the floor, then his daughter. "Yes", said Hengameh.

Bastinado is an old punishment which has been used in Iran for hundreds of years. The victim is put on their back with their legs in the air strapped to a horizontal wooden pole. The soles of the victim's feet are then lashed with whips.

While Firouz is good-humoured and stoic, Hengameh is filled with a righteous rage about the impotence of ordinary Iranians to effect change in the country.

Throughout our conversation, the television was on, murmering away quietly in the background. A newscast showed Mullahs involved in the preparations for the religious festival which was happening at the time. "Look at them, they're animals!" Hengameh exclaimed. "They're not religious, they're violent and they only want power."

Firouz served up delicious fried freshwater fish, local flatbread, rice and yogurt with aubergine and garlic. As we ate I asked both Hengameh and Firouz if they expected to see an end to the theocratic regime in their lifetimes. Firouz shrugged and said it was impossible to predict. Hengameh seemed more fatalistic: "The ones in power will do anything to keep their power. They are not the Iranian people. They don't care about anybody."

"How many journalists are in prison in Ireland?" Firouz asked. "None," I replied emphatically. "In Iran, two hundred and fifty," he responded drily, watching me for my reaction. Yes, I was shocked. Back at home, I've checked that statistic; Reporters Without Borders write in their 2008 annual report on Iran that "...the country remained the Middle East’s biggest prison for journalists, with more than 50 journalists jailed in 2007." Irrespective of the accuracy of Firouz' statistic, the contrast with Ireland is revealing.

It was three o'clock in the afternoon when we all gathered up our things to leave. I was really shaken by what I'd heard - it's one thing to read about human rights abuses, another thing entirely to speak to someone who's been on the receiving end of that abuse.

In Iran, people are subjected to brutal and arbitrary injustices. There is no free press. Anyone who dares to speak out is silenced. How galling it must be when the brutal regime claims to take its word from God to justify its exercise of power.

One afternoon, Aisling and I bumped into a father and his teenage daughter. Dad was carrying a bag of groceries. After exchanging the usual pleasantries, dad invited us to have lunch with them. "That'd be lovely," Aisling replied.

We walked on together, introducing ourselves. Dad's name is Firouz, his daughter Hengameh. Hengameh's English is good, Firouz's more rudimentary.

We arrived at their house and Firouz busied himself preparing first chay for everyone and later, lunch. As we sat around drinking chay, Firouz asked, "what's your opinion of the Iranian government?"

I tried to give a diplomatic reply, along the lines that in European media we read a very one-dimensional view of Iran, so part of the reason for our visit was to talk to ordinary Iranians to find out what the real story is. Firouz saw my reply for what it was, an attempt to side-step the question, chuckled, and then began slowly revealing his own opinion on Iranian politics and describing his experiences under the theocratic regime since the 1979 revolution.

Firouz was a young teacher at the time - in his early twenties - and was politically active. When the Islamic revolutionaries gained the upper hand, he was sacked from his job. Worse things happened, but I'm not going to mention those details - they could be used to identify the people concerned.

All of this was mediated through Hengameh, who's fourteen.

Firouz didn't volunteer the information that he'd been tortured. I'd asked. Hengameh didn't know what the English word 'torture' meant, so I said "Bastinado?"

"Hah!" exclaimed Firouz and looked at the floor, then his daughter. "Yes", said Hengameh.

Bastinado is an old punishment which has been used in Iran for hundreds of years. The victim is put on their back with their legs in the air strapped to a horizontal wooden pole. The soles of the victim's feet are then lashed with whips.

While Firouz is good-humoured and stoic, Hengameh is filled with a righteous rage about the impotence of ordinary Iranians to effect change in the country.

Throughout our conversation, the television was on, murmering away quietly in the background. A newscast showed Mullahs involved in the preparations for the religious festival which was happening at the time. "Look at them, they're animals!" Hengameh exclaimed. "They're not religious, they're violent and they only want power."

Firouz served up delicious fried freshwater fish, local flatbread, rice and yogurt with aubergine and garlic. As we ate I asked both Hengameh and Firouz if they expected to see an end to the theocratic regime in their lifetimes. Firouz shrugged and said it was impossible to predict. Hengameh seemed more fatalistic: "The ones in power will do anything to keep their power. They are not the Iranian people. They don't care about anybody."

"How many journalists are in prison in Ireland?" Firouz asked. "None," I replied emphatically. "In Iran, two hundred and fifty," he responded drily, watching me for my reaction. Yes, I was shocked. Back at home, I've checked that statistic; Reporters Without Borders write in their 2008 annual report on Iran that "...the country remained the Middle East’s biggest prison for journalists, with more than 50 journalists jailed in 2007." Irrespective of the accuracy of Firouz' statistic, the contrast with Ireland is revealing.

It was three o'clock in the afternoon when we all gathered up our things to leave. I was really shaken by what I'd heard - it's one thing to read about human rights abuses, another thing entirely to speak to someone who's been on the receiving end of that abuse.

In Iran, people are subjected to brutal and arbitrary injustices. There is no free press. Anyone who dares to speak out is silenced. How galling it must be when the brutal regime claims to take its word from God to justify its exercise of power.

02 January 2009

Tourist hejab

During the early part of our trip, in Tehran and then Gilan province, we saw not a single non-Iranian tourist. In Esfahan we spotted a handful (mostly Asians, interestingly enough) and then more and more as time went on. Must have been something to do with our timing.

During the early part of our trip, in Tehran and then Gilan province, we saw not a single non-Iranian tourist. In Esfahan we spotted a handful (mostly Asians, interestingly enough) and then more and more as time went on. Must have been something to do with our timing.I was struck by how a minority of female tourists just didn't seem to understand hejab (mandated modest clothing), or else got it but chose to try to push it to the legal limit.

Stripping away all the baggage that hejab carries and avoiding any discussion of the rightness or wrongness of it, acceptable hejab in Iran boils down to a few really simple rules:

- It's the law in Iran.

- It applies to men and women, but not equally. For blokes, the only restrictions are no t-shirts and no shorts.

- Women have to cover their hair. A bit of fringe is OK.

- Women have to cover their bums with a long top or jacket, at least mid-thigh length.

- You can take off your coverings in your own private space.

I reckon the sloppy tourist dress really caught my eye because Aisling adopted hejab with as much style as possible (well, I would say that, wouldn't I?), copying the type of hejab worn by educated urban Irani women. She blended in really well; quite a few times I had to search for her in bazaars if her back was turned, because her veil and manteau (long overcoat) looked so much the part.

The thing about hejab is that although it's mandated by law in Iran, most Iranians will respect you for adopting hejab just like everyone else. Aisling was only ever treated with the greatest of courtesy; she wasn't subjected to leering, groping or inappropriate comments, even on the few occasions when she went wandering around the bazaars by herself. I have a suspicion that some of the tour group folks wouldn't have had the same mellow experience of Iran that Aisling did.

If you're resentful of the oppressive dess code, wouldn't you feel all the more annoyed if a local pulled you up because your dress wasn't modest enough? Better to treat it as Aisling did, as a necessary fancy dress, do it with as much style as possible.

Bootable USB stick: the verdict

Another one for the techies! This may fry your brain if you don't grok computers.

Another one for the techies! This may fry your brain if you don't grok computers.In an earlier post, I described that I'd put together a bootable USB stick with a complete operating system on it. I also described how to subvert the block on Flickr by using the Access Flickr Firefox Addon.

I used the stick most of the time in hotels and coffeenets (Internet cafes) and it was a life-saver. Plenty of the machines we used had all kinds of duff software on them and unpatched versions of Windows XP. The USB stick gave us excellent peace of mind. No matter where we were, we effectively had the same computer all the time - and that computer weighs just a few grams and lives in a trouser pocket.

Access Flickr worked a treat every time we tried to use it, so we could upload images to Flickr and blog them from there. We didn't have to worry about our passwords being hijacked by keyloggers.

Ubuntu always found the wired network and connected automatically; in one place I had to choose a wireless connection from a graphical drop-down and once I'd done that, connectivity was established.

I picked up a cheapo Compact Flash card reader, so between that and the bootable USB stick, I could grab files from the big camera, copy them temporarily to a hard disk for sorting, selection, editing and uploading to Flickr. At no stage did I have to care about other stuff that might be installed on existing hard disks, or worry about stuff cached by the browser.

I found that coffeenet proprieters were cool about letting me modify the BIOS on their boxes once they know I was booting Ubuntu; in hotel coffeenets, I'd just get permission from non-technical staff to insert the USB stick and help myself to BIOS config. Only one hotel had computers in which the BIOS was passsword-protected, and all of the machines I used had BIOSes which were recent enough to allow booting from USB devices.

Those were the pros; what about the cons?

The USB stick is supposed to allow changes to be persisted between boots; so for example if I install Access Flickr and say ClamAV, those items ought to be present the next time I booted off the stick. This wasn't the case - I need to understand why. In future I'll build the bootable stick using Ubuntu 8.10's built-in tool.

I found that on machines with 512Mb of RAM, Ubuntu tended to lock up after a short period of time (a few tens of minutes), probably due to hitting some memory limit. The problem didn't happen on machines with more RAM. Perhaps another reason to use Ubuntu's bootable USB creator.

Any time I wanted to use the bootable USB stick I had to go through a bit of a rigmarole:

- Power off the computer

- Insert the stick in a free USB port

- Start the machine and go straight into the BIOS

- If the BIOS was password-protected, get permission to make modifications

- Specify the boot order as follows: CD, USB, Internal disk. Sometimes this involved making changes in two places

- Save the BIOS changes and reboot again

- Wait for Ubuntu to boot up - this was slow enough on some machines

All in all, the pros outweighed the cons for me; I'd consider getting a larger capacity USB stick or a laptop drive in a USB enclosure the next time I go on holidays and have to rely on Internet Cafes.

Iranian transport

Here's what you'll see on Iran's roads: No Mercedes or other European prestige marques, except for Tehran police cars. No modern four-wheel drives. Still plenty of Paykans. Lots of Iran-built South Korean small to mid-size saloons. Peugeots. Plenty of luxury buses for intercity travel, but quite a few 1970s-era buses with chrome trim and odd lines. Sturdy, blocky minibuses. Indian-style trucks, virtually no articulated lorries.

Here's what you'll see on Iran's roads: No Mercedes or other European prestige marques, except for Tehran police cars. No modern four-wheel drives. Still plenty of Paykans. Lots of Iran-built South Korean small to mid-size saloons. Peugeots. Plenty of luxury buses for intercity travel, but quite a few 1970s-era buses with chrome trim and odd lines. Sturdy, blocky minibuses. Indian-style trucks, virtually no articulated lorries.

Seven years in the war

We got a lift today from a double-jobbing taxi driver who's also an army officer in his other job. He spent seven years fighting the Iraqis during the Iran/Iraq war and was injured three times. "Iran kheyli [very] bad," he told us again and again.

01 January 2009

Tupolev Tu154m emergency exit

We flew back from Shiraz to Tehran on one of these; I was pleased to read that there have only been three fatal accidents in Iran involving this aircraft type since 1993.

I'm a relaxed flyer but this plane had me squirming a bit on takeoff and landing.

I'm a relaxed flyer but this plane had me squirming a bit on takeoff and landing.

The mud-brick minaret at Kharanaq

This is the shaking minaret that we climbed in Kharanaq. I made it to the wide ledge two-thirds of the way up while Hassan and Ben sat with their bums on the top parapet.

Spinach omelette patties and camel meat stew

This is the meal we had in the village of Kharanaq, on a table laid with a pink check tablecloth as I described. Everything else in the village was mud-coloured :-)

"Givaneh!"

It's the month of Muharram in Iran and black-clad male Shia adherents are parading in the streets in preparation for the day of Ashura, which is the day on which the Shia saint Husayn was slain by troops of the Sunni Caliphate at the Battle of Karbala 1,329 years ago.

The anniversary is treated as a period of mourning; for weeks in advance, on bus journeys, we've been hearing monotone chants for hours on end grieving the loss of Imam Husayn. The event is covered on television as though Husayn was killed yesterday. Mullahs weep openly in television studios. Hours of programming are given over to the event.

A parade of several hundred men walked past our hotel in Shiraz yesterday. I went out onto the street to watch them. A lone drummer beat out a slow rhythm on a huge bass drum while the men chanted a monotone dirge. They each wielded a whip, made from several short lengths of chain attached to a wooden handle, ceremonially striking themselves over the shoulder and onto their backs in time to the drum. It was more a stroking, not a lashing. (It's no longer considered appropriate to break the skin.)

It was dark, but I stood on a raised grassy median strip in the middle of the busy road and tried to take some snaps in the available light. A man about my own age approached me. "Where are you from?" he asked. "Ireland," I replied. "Man Irlandiam."

"Givenah," he said scornfully. "They are foolish."

The anniversary is treated as a period of mourning; for weeks in advance, on bus journeys, we've been hearing monotone chants for hours on end grieving the loss of Imam Husayn. The event is covered on television as though Husayn was killed yesterday. Mullahs weep openly in television studios. Hours of programming are given over to the event.

A parade of several hundred men walked past our hotel in Shiraz yesterday. I went out onto the street to watch them. A lone drummer beat out a slow rhythm on a huge bass drum while the men chanted a monotone dirge. They each wielded a whip, made from several short lengths of chain attached to a wooden handle, ceremonially striking themselves over the shoulder and onto their backs in time to the drum. It was more a stroking, not a lashing. (It's no longer considered appropriate to break the skin.)

It was dark, but I stood on a raised grassy median strip in the middle of the busy road and tried to take some snaps in the available light. A man about my own age approached me. "Where are you from?" he asked. "Ireland," I replied. "Man Irlandiam."

"Givenah," he said scornfully. "They are foolish."

These are a few of my favourite things...

It's our last night here and we're tapping away on the hotel computer before getting a taxi to the airport. I want to write a final post about all the special memories that I have of Iran - almost all are positive. So here it goes; some will only make sense to me but this blog is also a diary to remind me of my time here...

- Fantastic warm Iranian people

- Flat-breads for breakfast with soft feta-like cheese, sliced tomatoes and cucumber, fried eggs, honey, cherry and carrot jam and chay.

- Juicy dates and walnut wheelbarrows

- Boxes of tissues

- 'Welcome to Iran' - 'How are you?' - 'What is your opinion of Iran?'

- Turquoise and yellow tiles

- Delight and appreciation of locals when Ben speaks in Farsi

- Traditional teahouses with open courtyards and takht

- Arched penciled eyebrows

- Clapped out taxis with entertaining swarthy drivers

- Pink papier-mache wall in Fuman

- Bus goodie-bags with tea cup and cake

- Neema listening to Ben's Farsi language lessons on his MP3 player

- Mirrored room for courting Muslim couples

- Male and female door knockers

- Salted cherries

- Total cosiness

- Women clasping their chadors between their teeth

- Our rug-filled room in Masuleh

- Domed vaulted ceilings

- Saffron and white rice served with a butter patty

- Beautiful Farsi script

- Dust and pollution

- Bride wearing an elaborate white gown with a black and gold decorated chador

- Dizi

- Forks and spoons and no knives

- Decorative wrought iron shutters

- Sheepskin dashboards

- Beer and Champagne listed on menus - 0.0% alcohol

- Jagged sugar lumps for tea

- Wads of dosh

- Twin rooms and lack of double beds

- Pomegranate and Pistachio trees

- Sickly looking child mannequins

- Having the place to ourselves - mostly tourist-free

- Disco-ball mirrored palace ballrooms

- Yogurt stew

- Stalactite mouldings

- and blue mosque façades against sky at dusk.

Mohammad Reza in Jolfa, Esfahan

This is Mohammad Reza, enjoying food and conversation with us in the old Armenian quarter of Esfahan. Dinner with random strangers? Only in Iran could you contemplate such a thing.

We were standing on a street corner in Jolfa in the dark, looking in the guide book for a restaurant that wasn't there anymore. I was wearing my tourist beacon. Mohammad Reza approached us and asked did we need help. We got into the usual introductory chat ("Where are you from, what do you do?") and after we'd wandered around for a bit and consulted the map several times, he confirmed that the restaurant we were looking for was definitely closed.

We asked him to suggest another restaurant to us and invited him to join us for some food. After protestations, he politely took us up on our offer.

Mohammad Reza is a material sciences student, studying in Esfahan but also a native of the city. He'd spend a year living in Vancouver when he was fifteen (his dad is a university professor) and going to school there. He'd loved it. He's 22 now and almost finished his course. We'd learned all this before we'd even found the restaurant. His English is excellent and he's a funny guy with a quirky sense of humour.

We had a great evening chatting about all kinds of subjects; towards the end of the evening, Mohammad told us how, as a rational fellow, he'd weighed up the evidence for and against God and had decided that Islam was the religion for him. Yes, he admitted, he was born into a Muslim family, but on balance he reckoned it was the religion with the best moral code.

He explained that Muslims don't believe in the Christian notion of the Trinity or in the divinity of Jesus ("There no God but Allah and Mohammad is his prophet") and when we got onto the topic of heaven and hell, I asked about the fate of unbelievers.

"Well," he said with a grin, "there are good Muslims who go to heaven and there are bad Muslims who go to hell. If you're born a Muslim, it's impossible to be unbeliever!"

We were standing on a street corner in Jolfa in the dark, looking in the guide book for a restaurant that wasn't there anymore. I was wearing my tourist beacon. Mohammad Reza approached us and asked did we need help. We got into the usual introductory chat ("Where are you from, what do you do?") and after we'd wandered around for a bit and consulted the map several times, he confirmed that the restaurant we were looking for was definitely closed.

We asked him to suggest another restaurant to us and invited him to join us for some food. After protestations, he politely took us up on our offer.

Mohammad Reza is a material sciences student, studying in Esfahan but also a native of the city. He'd spend a year living in Vancouver when he was fifteen (his dad is a university professor) and going to school there. He'd loved it. He's 22 now and almost finished his course. We'd learned all this before we'd even found the restaurant. His English is excellent and he's a funny guy with a quirky sense of humour.

We had a great evening chatting about all kinds of subjects; towards the end of the evening, Mohammad told us how, as a rational fellow, he'd weighed up the evidence for and against God and had decided that Islam was the religion for him. Yes, he admitted, he was born into a Muslim family, but on balance he reckoned it was the religion with the best moral code.

He explained that Muslims don't believe in the Christian notion of the Trinity or in the divinity of Jesus ("There no God but Allah and Mohammad is his prophet") and when we got onto the topic of heaven and hell, I asked about the fate of unbelievers.

"Well," he said with a grin, "there are good Muslims who go to heaven and there are bad Muslims who go to hell. If you're born a Muslim, it's impossible to be unbeliever!"

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)